Vaginal mesh: From bad to worse?

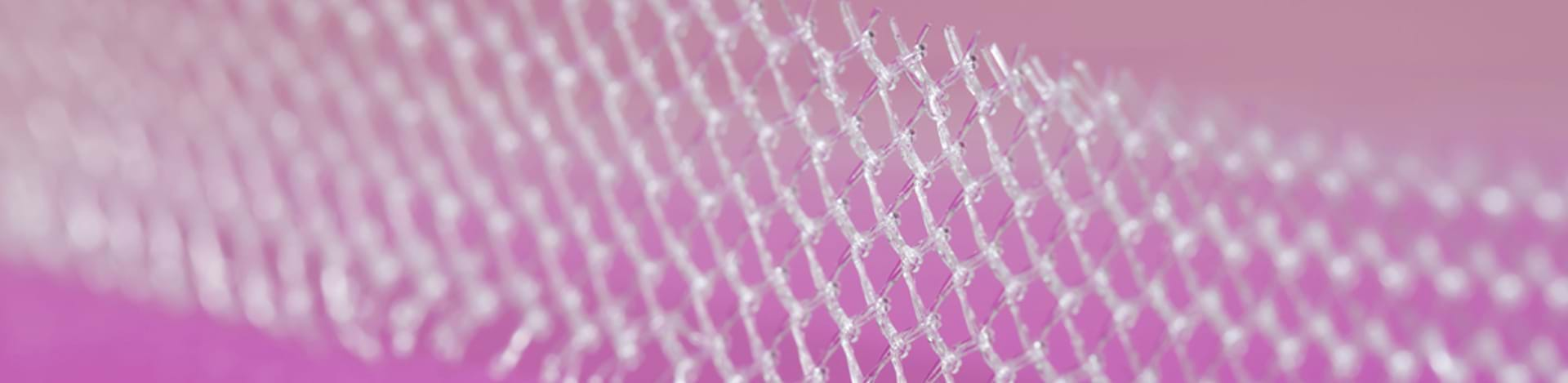

Since we first discussed the dangers of mesh implants, the controversy surrounding them has grown considerably, namely around the use of vaginal mesh implants. The mesh, made out of polypropylene plastic, the same plastic used in drinks bottles, has left women with chronic pain, unable to have work or even have sex as the mesh erodes, stiffens and cuts through organs such as the bladder. The controversy has only increased with the death of a major campaigner against vaginal mesh implants: Chrissy Brajcic. A number of countries have begun to impose bans on the implants, and there are discussions on whether to do the same in England. So what is the extent of the issue? And what can be done to improve matters?

What is vaginal mesh?

Vaginal mesh, also known as trans-vaginal tape (TVT), is used in the treatment of prolapse or urinary incontinence following childbirth. For the majority, this procedure is quick and successful. However, increasing numbers of women are coming forward with stories of debilitating conditions as a result of the implants, such as perforated organs, severe pelvic pain or erosion of the vaginal wall by the mesh. Unfortunately this can often be irreversible, with the mesh too close to nerves for it to be removed, or with damage having already been done by the time it is taken out.

For these injured women, the procedure can be life-changing, and many argue that up until now there has not been sufficient recognition of the dangers involved. Often, women were not warned of the risk of mesh implants, with some saying that they were only warned of the dangers of the anaesthetic, not the implant itself.

The issue in fact goes deeper than the patients themselves, as a BBC Panorama investigation found that it was not just patients who were ill-informed, but also doctors themselves. The investigation discovered that one of the biggest medical companies in the world, Ethicon (owned by Johnson & Johnson), failed to update their information on the complications posed by mesh implants, which would have kept patients and doctors more informed.

What is the NHS doing about it?

In England, debate still surrounds whether the implants should be banned or stay in use. MPs such as Owen Smith are campaigning for mesh to be banned in the UK. Yet the UK regulator, the MHRA, insists that the majority of women do not have issues, and they claim the complication rate is between 1-3%, rather than the 10% shown by the latest NHS figures.

There is some positive news on the horizon, as the UK medical watchdog NICE have recommend effectively banning mesh for prolapse surgery, restricting it to research only. This latest guidance says that current evidence shows that there are ‘serious but well-recognised safety concerns’ surrounding vaginal mesh. While the NHS do not have to take up this recommendation, it is said to be ‘highly likely’ that they will.

However, NICE’s recommendations only cover the use of mesh in prolapse, they don’t apply to the use of mesh for incontinence, which is what the majority of mesh operations are for.

What is being done elsewhere?

Whether or not NHS England chooses to implement this, they are quite slow off the mark in taking action amongst the increasing controversy. At the end of November, Australia restricted the use of vaginal mesh implants. A review in the country found that the benefits did not outweigh the risks of the procedure, and as a result they chose to remove their use in the treatment of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Following this, New Zealand have also banned the use of vaginal mesh implants for both prolapse and incontinence treatment.

Around the world litigation against vaginal mesh implants has grown considerably, and it is becoming clear that this is a much more widespread issue than was initially thought.

Is there any alternative?

Until the recent controversy, vaginal mesh implants were seen as the quickest and simplest way to fix issues of prolapse and incontinence following childbirth. However, with the growing awareness of the dangers involved, many are understandably looking into alternatives.

The first line of treatment recommended for prolapse is to try pelvic floor exercises and pessaries. If you do need surgery, then there are standard operations available which do not use mesh. A recent study by PROSPECT found that ‘women were just as likely to be cured after standard surgery rather than reinforced [mesh] repairs.’

Getting help after vaginal mesh injuries

If you believe you have been injured as a result of a vaginal mesh procedure then it is important that you seek medical help. Although it is not always possible to fix the issue entirely, you may benefit from pain relief and therapy to help you recover.

You may have a claim for medical negligence if this procedure was carried out without you being made aware of the dangers involved. If you wish to speak to one of our expert advisors, you can call us on the number at the top of your screen, or fill in our enquiry form.